Performance Posits Cyberspace as Darwinian Species

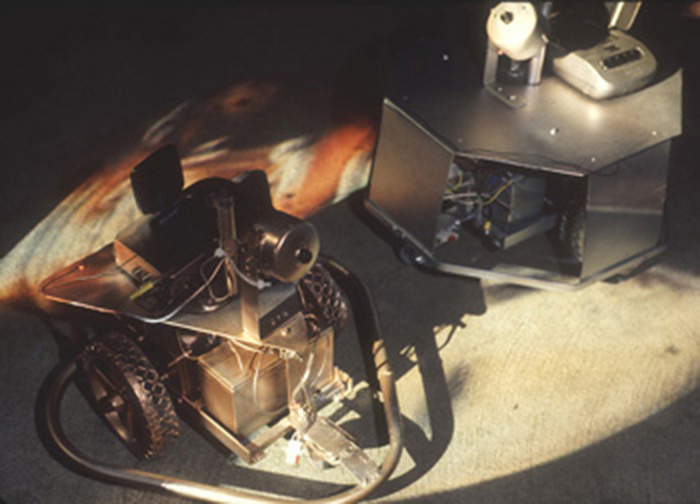

Credit: J. Betancourt. A robot from Sayonara Diaorama.

March 26, 1998

By MATTHEW MIRAPAUL

Performance Posits Cyberspace as Darwinian Species

When Adrianne Wortzel was learning in the 1980’s to draw animals, she would capture tigers, wolves and other wild creatures as a way to study their shapes.

But the artist was not on safari. Wortzel would point her camera at the glass-fronted habitats inside the Museum of Natural History on Central Park West in New York and turn the stilled lives into photographic still lifes, recording fixed images of the already-preserved beasts.

Now, Wortzel is ready to bid adieu to all that in Sayonara Diorama, an hour-long performance piece about cyberspace to be staged live at 8 p.m. March 28 and April 4 at Lehman College in the Bronx and, not at all incidentally, viewable in real time on the Internet.

Wortzel maintains that we glorify certain moments and romanticize them out of proportion to all others. Etched in the mind’s eye, these frozen tableaux could be as prosaic as last week’s call to tech support or as poetic as a fondly recalled theater matinee from 1949.

And, as Wortzel started to realize during her obviously redundant museum exercise, they also might include artistic acts that are overly infatuated with a finished product.

“When I was painting,” Wortzel said recently in a telephone conversation from her Manhattan home, “the end of the painting led to a conclusion, and then it had to stretch into as transcendent a situation as it possibly could.”

In creating and producing “Sayonara Diorama,” Wortzel continued, she is saying farewell “to that still moment that we’re all in love with, the still moment from which we analyze everything about anything. I’m much more interested now in process than in product.”

Although “Sayonara Diorama” is concerned with evolution — Charles Darwin, after all, is the main character — the fluid elements of the work reside more in its presentation than in its content.

Unlike Web-driven plays that rely upon surfer submissions for character development and onstage dialogue, there is a script (which has been posted on the Web), and the half-dozen human performers have assigned roles, as do the two or three robot actors that Wortzel designed.

But because the work’s premiere performances will be cybercast using the two-way CU-SeeMe videoconferencing software, they have the potential to become dynamically interactive.

Online viewers who are so inclined and sufficiently equipped can join — in a virtual fashion — the audience in the 500-seat Lovinger Theater, where projectors will cast their online images on the walls. The staff at Ellipsis, an avant-garde publishing house in London, has vowed to electronically alter the digital feed of the performance and send it back to the hall. A camera also will scan the seats, displaying its findings on a screen and perhaps on the Net.

“It will be quite lovely,” Wortzel asserted, “because it will mean that everyone can be present and everyone can be seen.”

“I have this vision of a huge global [networked computing] machine taking advantage of all kinds of collaborative situations to do theater, using everything from CU-SeeMe to satellite technology, everywhere from streets to cathedrals,” she continued.

“In this case, it’s an acting out of the real-time possibilities of combinations of online and offline theatrics. What this [play] does is pretend that outside and inside are the same thing. It asks, what does ‘present’ mean for all the parties?”

“And the actors can feel they’re playing to the entire world,” she said.

The piece’s full title is “Globe Theater: Sayonara Diorama,” a reference both to the reach of the Internet and to the site where many of Shakespeare’s plays were first performed. (“If the space of all the world is a stage,” Wortzel has written on her site, “then cyberspace may be the ultimate amphitheater.”)

“Sayonara Diorama” is the fourth work in Wortzel’s Globe series, but marks her first full-fledged theatrical staging after she built active installations for such locales as the Ars Electronica festival and the Art at the Anchorage event. She anticipates crafting five more “scenes” after “Sayonara Diorama.”

The current work is a futuristic fable set in the past. Darwin has returned to the seas 30 years after the voyage of the H.M.S. Beagle that ended in 1836. On the original trip, the diversity of life he discovered on the Galapagos Islands, some 600 miles off the South American coast in the Pacific Ocean, led him to develop the fundamental theory of evolution.

On this voyage, though, he is shipwrecked. After a singing robot’s opening aria, Darwin finds himself in a strange land where he encounters various monsters and the mythical Pandora. Still the dedicated scientist, he initially examines the creatures; eventually, he interacts with them. Ultimately, a new species is born.

Wortzel readily acknowledged that the strange new world is cyberspace, and that the scenario is her assertion “that all this technology doesn’t have to homogenize. It can actually deepen differences and diversity and make it richer for everybody.”

Although the script contains many lines such as “another off-the-rack paradigm for our epistemological stew,” Wortzel does have a penchant for clever puns and tricky anagrams. The name of Darwin’s character, for example, is “Clan-Is-Raw-Herd.”

In addition to the onstage and online action, “Sayonara Diorama” uses video to provide a visual backdrop; among its images are Wortzel’s museum photographs.

Wortzel, an artist in residence at Lehman, teaches at the School of Visual Arts and the Cooper Union. She publishes regularly on and off the Web, where she explores the relationship between electronic media and more traditional forms.

Matthew Drutt, associate curator for research at the Guggenheim Museum, will participate in a post-performance panel on March 28.

“Adrianne’s aesthetic prowess lies both in her theoretical approach and in how she manipulates technology to express a range of complex ideas. Her work seamlessly weaves contemporary issues together with ancient, medieval, Renaissance, Enlightenment and 19th-century conceptions of humanity,” Drutt said.

And, in “Sayonara Diorama,” a little bit of Broadway, too.

“I want everyone to be inspired about the future,” Wortzel said. “It’s sort of like going to musical comedy. They’re hopeful. When you come out, you’re singing a song and feeling reconnected.”

Eyeing one of her own frozen tableaux, Wortzel recalled seeing as a child the original production of a musical by Rodgers and Hammerstein. Just as Darwin journeyed to the Galapagos Islands, Wortzel visited the version of “South Pacific” that opened in 1949, starring Mary Martin.

Years later, Wortzel became friends with Martin. She opined that the actress, if still alive to see it, would probably enjoy how the theater has continued to evolve while retaining some essential ingredients.

Wortzel said, “She [Martin] wouldn’t get the online part. She would probably say, ‘What are those fuzzy pictures?’ But she would like the play. It’s very lively and very human. The words are ideological, but the characters are as real as we can get them to be.”

arts@large is published on Thursdays. Click here for a list of links to other columns in the series.